From the first back-of-the-envelope sketches to the design of Scopus AI, collaboration has guided the database’s evolution

This month marks the 20th birthday of Elsevier’s abstract and citation database Scopus. The intervening years have seen huge shifts in the solution’s technology, capabilities and content. But its focus on innovation is a factor that has remained constant, according to Product Owner Yoshiko Kakita.

“Staying ahead of the curve is critical for our team. We want to identify emerging trends in the community early on,” Yoshiko says. “By addressing these trends before they become significant to the community, we can be well prepared to support important customer needs effectively.”

Yoshiko points to the recent release of recent release of Scopus AI as a great example. This generative AI tool enables users to ask academic questions using everyday language. It then uses the content in Scopus to generate referenced summaries and additional insights.

“We did not build it because our customers explicitly asked for an AI tool,” she admits. “But we know from our years of working closely together that they have pain points this technology can address.”

One of these is finding a way to sift through the large volume of published literature out there. “We could see a definite need from a search and discovery perspective,” says Yoshiko.

Another pain point is the difficulty of collaborating with researchers in other domains. “There is a growing interest in multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary research to drive innovation and meet societal challenges,” explains Yoshiko. “However, researchers tell us that crossing disciplinary borders is challenging. Let’s imagine I want to get to know your research area. First, I need to know the keywords so that I can find relevant articles. Then I have to digest information from abstracts in an area that may be completely different from my own. Only then can we start our conversation properly. Scopus AI meets these needs by helping researchers understand a new topic quickly.”

This month sees Scopus AI add a new response feature – Emerging Themes: “Researchers spend a lot of time finding new research themes. Using a sophisticated algorithm we’ve developed, this feature identifies three types of trends – consistent, emerging and novel. This helps researchers quickly identify where the most promising opportunities lie. And based on user interviews so far, we know they find it very valuable.”

While academics may not have directly requested Scopus AI, they were heavily involved in its development. “We started to engage with our Scopus customers even before we released the alpha version in August 2023,” recalls Yoshiko. “Then, every time we built a prototype, we tested it with them and iterated on it very quickly. And luckily for us, they were eager to engage and give honest feedback.”

The Scopus AI team continues to gather feedback from a broad cross-section of researchers, librarians and academic leaders daily. All comments, whether positive or negative, are carefully reviewed by team members.

But while it’s easy to action consistent feedback, it’s when views differ that things get complex, says Yoshiko. “One of the areas that divides opinion the most is whether we should use citations to select content for Scopus AI’s responses – we don’t at the moment. And so far, the majority of customers say that using citations in this way would be a form of confirmation bias. However, in some countries and regions, views differ. For us, the challenge is finding a way to address everyone’s requirements – but we will!”

Working collaboratively with the academic community on Scopus is nothing new. In fact, the first iteration of Scopus back in 2003 was built using an “evidence-based development” approach that saw Elsevier partner with 21 institutions and hundreds more individuals to test and iterate.

It’s a process that Elsevier’s Sandra Power, who liaised with many of those partners, remembers well. Sandra, who now works marketing Scopus and SciVal in North America, recalls it as an exciting time, filled with possibility. “All of us in the team felt like we were working on something innovative. Scopus was really one of the stepping stones that saw Elsevier evolve from a publisher into a data analytics company.”

She adds: “The user testing we conducted was extensive – to be honest, I really think that’s one of Elsevier’s strengths. Our goals were to understand what they needed and how they interacted with research. We wanted to make sure what we were developing was what they were looking for.”

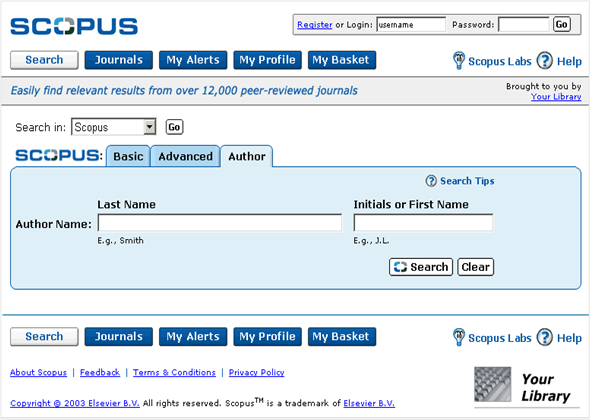

The feedback they received helped to shape the Scopus we see today. For example, it was soon clear that while people were excited about the publication content, they were equally interested in the authors of those publications. That led the development team to enhance the ‘search by author’ functionality and make it easier to view information on individual authors.

That early work on building author content laid the foundation stones for the introduction of the Scopus author profiles in 2006 – today, Scopus is home to 19.6+ million of them. According to Yoshiko, the release of those profiles was one of many Scopus developments that helped her team move so quickly in response to the launch of OpenAI’s ChatGPT tool in November 2022.

Generative AI was still a relatively little-known technology outside of product circles prior to that launch. But within just months of ChatGPT appearing in the market, Elsevier had built the first protype of Scopus AI. A few months later, Elsevier had released it as one of the first academic generative AI tools on the market. According to Yoshiko: “Scopus AI is very much related to the Scopus 20th birthday story, because it’s the improvements introduced since the launch of Scopus that made it possible.”

Two other critical developments she points to are the release of the organization profiles in 2007, and the sophisticated knowledge graph that connects all the rich data and entities in Scopus. Another important innovation was the vector search that Scopus AI draws on – this technology uses semantics to identify relevant content, improving the relevancy of responses. Yoshiko explains: “Luckily for us, the Scopus knowledge discovery team saw this new vector technology on the horizon and started investing in it back in 2022.”

But technical preparedness wasn’t the only factor behind the rapid launch of Scopus AI. Yoshiko believes that team culture also played an important role. “We aren’t afraid to take risks – we are willing to learn by trial and error.”

Another crucial factor was the product team’s desire to provide the academic community with a tool they can trust. “Yes, there were business considerations in wanting to be the first to market. But equally important was the knowledge that combining this disruptive technology with a high-quality content source like Scopus, could benefit the community,” explains Yoshiko.

“There was a lot of discussion back then about whether academia should use ChatGPT and generative AI tools. Some were expressing concerns about their use, while others were acknowledging their potential. We wanted to advance the conversation in a meaningful way.

“Introducing Scopus AI gave the community something concrete, based on content they knew and trusted, that they could try. It also gave them someone they could express their concerns about too, and we took those concerns on board and used them to improve our technology. We continue to do that today.”

“While a lot of people can build generative AI tools, not everyone has access to quality content like ours. Technology can be copied in hours, but the kind of curated, peer-reviewed database that Scopus AI is built upon takes years to develop.”

For Yoshiko there are two major trends likely to prove game changers for academia in the coming years. “Generative AI is definitely one of them. No-one knows yet where it will take us, but I believe we are in the middle of this big shift and our goal is to continue evolving Scopus to support it.”

Yoshiko also sees a role for Scopus AI in helping institutions become “AI ready”. She says: “Some organizations are still at an early stage, but I think that readiness will become increasingly important for competitive reasons.” She adds: “Being AI ready isn’t just about understanding the tools and the technology, it’s about being aware of all the other aspects, such as AI ethics, impacts etc. And as our Responsible AI Principles show, these are major focus areas for us.”

The other potential game changer for Yoshiko is how research, and researchers, are evaluated. “Until now, there has been a focus on publications and citations, etc., but beyond bibliometrics there is an increasing focus on societal impact, research culture and how research is done. One of the ways that Scopus is addressing this shift is by incorporating the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Today, you can visit any Scopus author or institution profile and if their work is contributing to the SDGs, it will tell you, and flag which goals they are connected to.”

She adds: “This is one of those areas where we are trying to be ahead of the curve. Although our discussions with researchers show the SDGs aren’t necessarily a big focus for them yet, we know they are for governments and funders, so customer interest will increase. And maybe by highlighting the SDGs in Scopus we can help to engage those researchers – if we can contribute to making a difference in that way, well, that’s what makes us happy.”